3 Ships Arrived in Philadelphia in 1717 Carrying 80 Families

Reader-Nominated Topic

European settlement of the region on both sides of the Delaware River dates to the early on seventeenth century. The population grew apace afterwards 1682, when Pennsylvania'due south policy of religious tolerance and its reputation as the "best poor man's state" attracted people from all walks of life. By the time of the American Revolution, Philadelphia was the largest city in colonial America. With a population above 32,000, it was noticeably larger than the adjacent two largest cities, New York (25,000) and Boston (xvi,000). Its size was near entirely the result of migration from Europe, Africa, and other American colonies.

Settlers—both voluntarily and involuntarily—came to Philadelphia and the surrounding region from England, Wales, Ireland, Scotland, German language-speaking lands in the Holy Roman Empire, France, Kingdom of the netherlands, Kingdom of spain, Sweden, the west coast of Africa, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and the Caribbean. They were Quakers, Presbyterians, Lutherans, German Reformed, Baptists, Anglicans, Catholics, Jews, possibly some Muslims, and others from a variety of smaller religious sects. Some were wealthy, many more arrived as artisans, laborers, small farmers, or servants hoping to make their fortunes, and many came unwillingly as enslaved Africans. Philadelphia even had its share of pirates (of which very little is known).

Founded in 1764, the High german Social club helped recent German immigrants find employment, housing, and other German language-linguistic communication resources throughout Philadelphia.

(Library Company of Philadelphia)

In many ways the founder of Pennsylvania, William Penn (1644-1718), designed the province to exist socially and economically diverse. He envisioned a utopian order, ane in which differences of opinion and backgrounds would naturally create a stable and tolerant society. In his 1670 "The Keen Case of Liberty of Conscience," Penn articulated these behavior on the necessity of a religiously tolerant society. A few years later, in 1675, Penn noted in his "England'south Nowadays Interest Considered" that the suppression of religious dissent created disorder, while religious multifariousness and freedom enabled a more ordered, peaceful gild. To that end Penn invited persecuted religious groups from other nations to settle in Pennsylvania. He made voyages to continental Europe in 1671, 1677, and 1686 in part to recruit settlers. He wrote four works specifically intended for Dutch and Germans that were later translated and circulated. Penn recruited the mistreated to Pennsylvania to ensure a wide range of religious and ethnic interests to meet his societal goals.

Pre-Penn, a Stable European Population

By the time of Penn's arrival in Pennsylvania in 1682, the inhabitants included Native Americans every bit well as some 600 Swedes, Finns, Dutch, and Germans—including some who had settled every bit early as 1638, when the westward side of the Delaware River belonged to New Sweden. When New Sweden became incorporated into New Amsterdam in 1655, the number of Dutch increased. The European population and so remained stable and its relations with Native Americans limited until Penn received his charter for Pennsylvania in 1681. Seventeen years before, the Duke of York gave the due east side of the Delaware River (what is now New Jersey) to Lord Berkeley (1602-78) and Sir George Carteret (1610-80); the sometime sold his plot to Quaker John Fenwick (1618-83). In the late 1670s under Penn'south guidance, more than 1,000 Quakers from London, Kent, and Yorkshire settled W New Jersey and established towns in Salem and Burlington.

Penn arrived on the shipWelcome on October 27, 1682, with near 100 other Quakers. On the westward side of the Delaware they joined some other 100 recently settled Quakers who had established two meetinghouses near what would be Philadelphia. These Quakers were of English, Welsh, Irish gaelic, and High german descent and speedily took over the institution of government in the new Pennsylvania. In addition, Penn sold plots of land to wealthy Quaker investors, mostly of English descent. A few Welsh Quakers bought 40,000 acres of land on the other side of the Schuylkill River, historically known every bit the "Welsh Tract," and established the towns of Haverford, Merion, and Radnor. Other Quakers established the towns of Darby, Chichester, and Concord west of the metropolis, all in the early 1680s. Penn also authorized the naturalization of the preexisting Dutch, Swede, and Finnish inhabitants, some of whom took him up on the offer.

In the starting time decades nether Quaker leadership, Philadelphia became a major port city and a booming trade centre, which encouraged migration by merchants and tradesmen coming from England and Wales. Past 1700, central Philadelphia grew from a small collection of Swedish homesteads to a population of approximately 2,000 concentrated in a half-mile broad stretch along the Delaware River that extended four blocks inland. Pennsylvania as a whole grew from 680 to almost xviii,000 European residents; New Jersey grew from i,000 to xiv,000 Europeans; and the lower counties on the Delaware (afterward the state of Delaware, too controlled by Penn) grew from near 200 to nearly 2,500 Europeans by 1700. As trade increased, skilled craftsmen, more often than not Quakers, migrated to Philadelphia to do the work of construction, send building, masonry, carpentry and other service needs of the growing city. Opportunity also attracted farmers, weavers, and millers, who moved to the available hinterland.

Prospects for Progress Drew the Poor

The mercantile possibilities of Philadelphia attracted poor, single young men and some women in search of their fortunes. These redemptioners signed contracts for between i and 4 years of service in exchange for their voyages. Even more signed indentured-servant contracts, which bound them to up to seven years of service. Some arrived with their masters as part of the family. If they served out their term, they gained 50 acres of state, some tools, and another ready of clothing. However, every bit historian Sharon Salinger noted, four men migrated for every woman, leading to a very uneven gender ratio in seventeenth-century Pennsylvania.

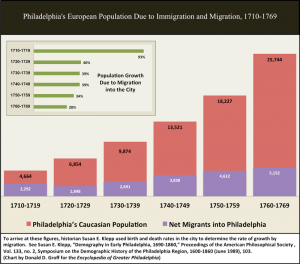

Philadelphia'south demographics inverse drastically in the first half of the eighteenth century. Immigrants from western Europe arrived in search of state and religious freedom. Migrants from other colonies came in search of greater, or maybe simply the next, opportunities. Philadelphia experienced exponential growth through the influx of thousands of Germans, Scots Irish, English, and hundreds of enslaved and some free Africans. In 1710, at the start of the influx, Philadelphia contained 2,684 residents. By 1740 that number more tripled to ten,117, and past 1775 the population tripled again to 32,073. As historical demographer Susan Klepp's inquiry shows, Philadelphia's

Chart i. Philadelphia'south European Population Due to Clearing and Migration, 1710-1769. [Click prototype to enlarge]

Caucasian population had a small-scale x to 15 percent increase from 1700 to 1710. Then from 1710 to 1740, Philadelphia'south Caucasian population grew about a 3rd each decade. In an era of high bloodshed and depression nascence rate, most of this increase was due to migration and immigration (come across Chart 1).

More than than x,000 new settlers arrived annually into the port of Philadelphia. Well-nigh moved on to land in Lancaster, York, Berks, and Bucks counties, while only 10 to xx percent remained

Chart 2. Estimated Ethnic Composition of Philadelphia past Population, 1700-1769. [Click image to enlarge]

in the city. While migration made the city more crowded and diverse, many surrounding towns remainedrelativelyethnically and religiously homogenous in cases in which whole towns from Europe migrated en masse. Philadelphia quickly became a city in which no grouping, including the English language, had a majority (see Nautical chart two), but the same could non be said for all of the mid-Atlantic. For case, as Stephanie Grauman Wolf has shown, Germantown was eighty percentage German even though information technology included a diversity of other settlers.

Migration From Colony to Colony

Migration was a office of colonial American life. Eighteenth-century American colonists searched for better opportunities, especially from state-crowded New England and religiously troubled Maryland and Virginia. Benjamin Franklin (1706-xc) is maybe the nigh famous example of such a migrant. Other Americans wandered (mostly walked) into Philadelphia and other parts of Pennsylvania in search of their fortunes. As historian James Lemon noted, nearly one-half of the population of Philadelphia, and other surrounding towns, migrated every ten years. Of those migrant Philadelphians whose origins in North America (including English language Caribbean colonies) have been firmly established betwixt 1700 and 1740, approximately 17 percent originally arrived in Maryland, 17 percent in Virginia, 11 percentage in New York or New Bailiwick of jersey, 17 percent in New England, and 38 pct in the Caribbean. Although migrants often moved several times in their lives, records rarely exist for those multiple transitions. The brief appearances of migrants in the records reveal a full general migration towards cities, then continually westward.

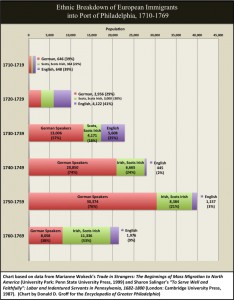

Nautical chart 3. Indigenous Breakdown of Europeans Immigrants into Port of Philadelphia, 1710-1769. [Click image to enlarge]

Transatlantic immigrants to Philadelphia left from the ports of Belfast, Derry, Larne, Portrush, and Newry, in Ulster, Cork, and Kinsale in Southern Republic of ireland; London, Portsmouth, and Plymouth in England; Rotterdam and Amsterdam in the Netherlands, often with stops along the fashion in the Caribbean and Delaware. Although colonial migration records are incomplete, historians Marianne Wokeck and Sharon Salinger examined the port records in North America and in Europe that listed ports of origin, and from that information determined the likely ethnic breakdown for most of the European migrants arriving in Philadelphia between 1710 and 1769 (see Nautical chart three). Immigrants in this period were mostly from German-speaking areas, although in the 1710s and 1720s English immigrants dominated, and in the 1720s and 1760s waves of Scots Irish and Irish temporarily contradistinct earlier clearing patterns.

Chart four. Estimated Ethnic Composition of Philadelphia by Percentage, 1700-1769. [Click paradigm to enlarge]

The ethnic breakdown on European immigration into the port of Philadelphia (Nautical chart iii) suggests the white indigenous variety of the mid-Atlantic region. All the same, the population of the city of Philadelphia did not match the demographic composition of the arrivals to its port (Encounter Chart 2 and Nautical chart 4). Merely a pocket-sized percentage of the total arrivals settled in Philadelphia; the city's population remained steadily English until the 1730s, when the Irish gaelic and German language-speaking immigrants became a majority of the population.

Near migrants traveled to Pennsylvania during periods of European crises. The biggest migration years—1709, 1717, 1727, 1738, and 1749—related to external events. For instance, equally historian Marianne Wokeck noted, the end of the War of Austrian Succession in 1749 correlated with a abrupt increase in migration from the regions affected by the war. Farther, Pennsylvanian booster literature encouraged German-speaking religious groups to migrate. These promoters emphasized material advocacy and a fix welcome to migrants.

Immigrants Arrived equally Family unit Groups

During the 1710s through the 1730s, immigrants sometimes traveled in family groups, or followed earlier arrivals and settled with them to get assist in establishing households in the new colony. Wokeck noted that at least 35 percent of German-speaking migrants traveled in family groups. This chain migration revealed the strong want of colonists to describe in others from Europe. The immigrants relied on these contacts to pay for their ship passage. In a process called redemption, they signed contracts for ship passage in commutation for either labor or payment at the end of the voyage. They hoped a friend or kin would pay for the voyage upon their arrival. Germans often redeemed other German-speaking migrants, fifty-fifty strangers.

Despite the prosperity that migrants brought to Pennsylvania, Philadelphians, peculiarly those in positions of wealth and authority, distrusted these new, non-English language, arrivals. In 1717, Governor William Keith (1669-1749) recommended to the Provincial Associates to not "lose any Time in securing yourselves, and all the People of this colony, from the inconveniences which may perchance arise by the unlimited Number of Foreigners that… have been transported here of late." The governor believed that migrants would cause harm to Philadelphians. In 1718, James Logan (1674-1751) resolved that "nosotros are resolved to receive no more of them." In 1727, the Pennsylvania Associates asserted that "the swell Importation of Foreigners into this Province… who are subjects of a foreign Prince, and who keep upward amidst themselves a dissimilar Language, may, in Fourth dimension, bear witness of dangerous Issue to the Peace." To the Associates, foreign migrants were non symbols of a prosperous economy, but a danger. The Provincial Council tried to assuage elite fears by controlling migration. In 1717, the Provincial Council imposed a tax on all incoming Palatines. In 1718, the Provincial Council requested that ship merchants listing their passengers, and that all foreigners swear an adjuration to the King—a requirement not always faithfully observed. These two acts did not curtail migration from Europe.

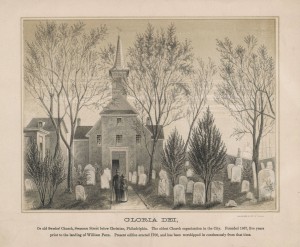

Swedish Lutherans who settled along the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers founded Gloria Dei (Old Swedes') Church, congenital near nowadays-day Christian Street and Columbus Boulevard, in 1677. (Library Company of Philadelphia)

The other major migrant groups to settle in Philadelphia after 1710 came from Republic of ireland. Historians and demographers normally identify them every bit "Irish." Although most Irish migrants were Presbyterian, they also included Anglicans, Baptists, Quakers, and Catholics. Those from Northern Republic of ireland were Scottish Presbyterian transplants to Ireland labeled "Scots Irish" or "Ulster Scots." Those from southern Ireland were more often than not Catholic and labeled only "Irish." Altogether, approximately vii,500 Scots Irish and Irish migrants arrived in Pennsylvania before 1740; about 20,000 in the American colonies. Merely well-nigh 20 percent of these migrants resided in Philadelphia. The rest continued to rural Pennsylvania, founding the town of Carlisle, for instance, in the 1750s. Between 1710 and 1740, Philadelphia's Irish gaelic and Scots Irish population grew from 600 to over ii,600 residents, consisting of between 20 and 27 percent of the total population (see Chart 2 and Chart 4). Every bit historian Patrick Griffin noted, this population grew then much considering Scots Irish and Irish migrants reported inexpensive, plentiful, and bountiful state to their friends and family in Ireland. It was too desirable because Pennsylvania lay on a major merchandise route, needed weavers and linen workers, and housed the only Presbytery in North America.

Migrants every bit Buffers

Elite Pennsylvanians initially welcomed Scots Irish and Irish migrants in the promise that they would move to the countryside, creating a buffer between Native Americans and the already settled Pennsylvanians. However, they also worried that Irish and Scots Irish gaelic beliefs could destroy peaceable relations with the Delaware Indians. In the city, elites blamed recent Irish and Scots Irish gaelic migrants for drunken disorderliness.

Surprisingly, picayune is known about eighteenth-century English migration into Pennsylvania. Nigh 14,000 English migrants sailed into the port of Philadelphia (see Chart 3). Different the German, Irish, or Scots Irish gaelic migrants, English arrivals did not concern Pennsylvania's residents. No one complained of an indentured servant or a recent migrant every bit English. On the other mitt, no one extolled the virtues of English migrants, either. Ane 3rd of these London-embarked migrants traveled equally indentured servants. Most of the travelers, servants or not, did non originate from London, simply from the far-flung countryside, many from Wales and the north of England, constantly looking for new opportunities.

Nearly 2,700 African slaves arrived in the port of Philadelphia by the eve of the American Revolution. Quakers eagerly bought the first group of slaves directly from Africa in 1684, totaling well-nigh 150 souls for immigration and building the city. Past 1705, nearly 7 percent of families endemic slaves. Many of the early on slaves (autonomously from the first 150) arrived from the Caribbean, but by mid-century they increasingly arrived straight from Africa. About slaves arrived in Philadelphia in 2 peak periods, from 1732 to 1741 when 510 slaves arrived, and from 1757 to 1766, when 1,290 slaves arrived. Slave importations increased when arrivals of indentured servants decreased and vice versa. Equally historians Gary Nash and Jean Soderlund take shown, the strength of European indentured servitude in the eighteenth century slowly eroded the importance of slave importation; in 1710, slaves constituted 10 percentage of the population, only but 3 percent by the time of the Revolution. Throughout, this Philadelphian slave population depended on slave importations to reproduce. Philadelphians of all socioeconomic levels bought slaves, and ii-thirds of Pennsylvania slaves lived and worked within the city. In the 20 years before the Revolution, slaves constituted between 2- thirds and 3-fourths of unfree labor in the metropolis. Philadelphians bought slaves to help in the household, but also as help in crafts and aboard maritime ships. The few slaves outside of Philadelphia were often bought as status symbols for a country estate. Rarely did farmers use slave labor, preferring to use European servants.

By the time of the Revolution, Philadelphia and the surrounding counties, Berks, Bucks, Cumberland, York, and parts of New Jersey, were ethnically, religiously, and economically diverse. Merely they were also continually changing. Migrants moved constantly in search of greater opportunities (the reasons they arrived in Philadelphia to begin with). This movement, despite the fears of some settlers, created an environment of acceptance. While no one would call information technology a pluralistic society (because the term was not mutual), people of multiple ethnicities and religions lived equally neighbors with very few conflicts, and enjoyed relative peace and prosperity.

Marie Basile McDanielis an Banana Professor of History at Southern Connecticut State University. This essay is based partly on her work for her dissertation, "We Shall Not Differ in Sky: Matrimony, Order and Identity in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia."

Continue to Immigration (1790-1860)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Fogleman, Aaron. Hopeful Journeys: High german Immigration, Settlement, and Political Culture in Colonial America, 1717-1775. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Printing, 1996.

Griffin, Patrick. The People with No Name: Republic of ireland's Ulster Scots, America's Scots Irish gaelic, and the Cosmos of a British Atlantic World 1689-1764. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Klepp, Susan E., ed. "Symposium on the Demographic History of the Philadelphia Region, 1600-1860." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133, no. 2 (1989).

Lemon, James. The All-time Poor Homo'due south Land: Early Southeastern Pennsylvania. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972.

Salinger, Sharon. "To Serve Well and Faithfully": Labor and Indentured Servants in Pennsylvania, 1682-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Schwartz, Sally. "A Mixed Multitude": The Struggle for Toleration in Colonial Pennsylvania. New York: New York University Press, 1987.

Wokeck, Marianne. Trade in Strangers: The Beginnings of Mass Migration to Northward America. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State Academy Press, 1999.

Church and Burial Ground collections, Genealogical Club of Pennsylvania, 2207 Anecdote Street, Philadelphia.

Abraham H. Cassel Collection and other collections, Historical Society of Philadelphia, 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia.

Pennsylvania Collection and other collections, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, State Athenaeum, 350 Northward Street, Harrisburg.

Glorei Dei Church building National Historic Site, 916 S. Swanson Street, Philadelphia.

Christ Church, Second and Market Streets, Philadelphia.

Source: https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/immigration-and-migration-colonial-era/

0 Response to "3 Ships Arrived in Philadelphia in 1717 Carrying 80 Families"

Post a Comment